South Korea Can Go Only So Far Copying Japan’s Market Reforms

Jacky Wong

Sep 25, 2024 (Gmt+09:00)

South Korea is taking a page from Japan to boost its stock market. There are certainly some low-hanging fruits to pick, but the country’s large family-controlled corporate empires, known as chaebols, could be an obstacle to more meaningful structural change.

The country’s stock exchange is set to unveil a stock index that will take into account factors such as profitability and shareholder returns. That is modeled after a similar move taken in 2014 by Japan, which uses its new index to essentially name and shame companies that failed to make the grade.

The new index is just a part of Korea’s “corporate value-up” program announced in February, aiming to boost the valuations of its market with shareholder-friendly policies. The government also proposed making changes to the tax code to encourage companies to pay more dividends. More broadly, South Korea hopes to copy the success of Japan’s drive to improve corporate governance and returns to investors.

Buybacks and dividends in Japan have risen, and shareholders have grown more vocal. Companies also are unloading their nonstrategic shareholdings in other companies, slimming down their balance sheets.

As a result, Japan has been one of the best-performing markets in the world in recent years. The Topix index hit a record high in July, nearly 35 years after its famous bubble burst.

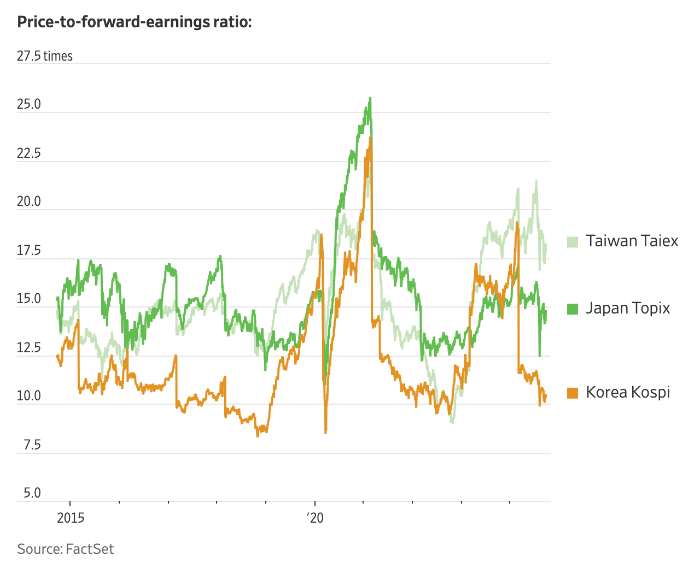

On the other hand, South Korea’s stock market has long suffered from a so-called Korea discount, as it trades more cheaply than other emerging markets. Its main benchmark, Kospi Composite index, has been valued at an average 12 times forward earnings in the past decade, compared with around 15 times for Japan’s Topix and Taiwan’s Taiex each.

Japan’s index has gained 40% since the end of 2022, while Taiwan’s has surged 57%. Korea’s, by contrast, has gone up only 16% over the same period.

Similar to their counterparts in Japan, Korean companies haven’t historically been willing to return much capital to shareholders. The dividend yield on the Kospi is below 2%, which is lower than many markets. Buybacks are paltry and, more important, many Korean companies don’t cancel the shares they have bought back, instead keeping them as treasury shares, using that as a tool for major shareholders to keep control of the company.

On that front, there seems to be some progress. Treasury share cancellation, excluding Samsung Electronics, so far this year has already more than doubled the full-year level of 2023, according to Goldman Sachs. New regulations restricting how companies can use their treasury shares is probably one reason. Financial companies, in particular, have been eager to buy back and cancel their shares.

The elephant in the room, however, is the power of chaebols, which dominate Korea’s economy and stock market. Companies in the Samsung group, for example, make up more than 20% of the Kospi index. Besides the electronics brand, this includes companies in areas as disparate as financial services and shipbuilding. The interests of the families who control these vast corporate empires don’t usually align with those of the minority shareholders.

Instead, they have long used convoluted corporate structures, including extensive cross-shareholdings, to maintain their grip on the conglomerates. Given the chaebols’ strong economic and political influence in the country, they won’t be so easily pressured as Japanese companies have been to unwind these arrangements.

High inheritance taxes are another reason the families might not necessarily want high share prices for their companies. The government has proposed reducing the tax, but it might not be enough.

Korea’ stock market, which houses some of the world’s best-known brands, including Samsung and Hyundai Motor, has long been a laggard. The government’s new push might yield some successes, but its biggest companies could remain the toughest nuts to crack.

Write to Jacky Wong at jacky.wong@wsj.com

More To Read

-

Mobility firms, banks replace battery, K-culture stocks in KEDI 30 Index

Sep 12, 2024 (Gmt+09:00)

-

South Korean stocks rebound but still on rollercoaster

Aug 06, 2024 (Gmt+09:00)

-

South Korean stock market crashes; more falls seen ahead

Aug 05, 2024 (Gmt+09:00)

-

S.Korean stocks log largest daily loss since pandemic

Aug 02, 2024 (Gmt+09:00)